Tuesday, 15 January 2013

How HMV can save itself

This is a piece I wrote almost exactly a year ago. I've left it intact as I think it's all still relevant, but please bear this in mind.

Not too long ago the flagship HMV shop on Oxford Street was a destination. If you were meeting someone in town you would arrange to hook up in the album section, maybe between B and D to browse the Beach Boys or Dinosaur Jr’s wares while your friend struggled with the vagaries of the Central Line. Those sections are still there, but the last people I arranged to meet in HMV were a pair of Fifties pop enthusiasts, both in their seventies, to whom a rendezvous at the store has become an old habit that they find hard to break.

The shop is so unattractive, and so unsure of its purpose, that it is wholly uninviting. I popped in at Christmas to buy some last-minute presents and breathed in what atmosphere there was. I saw two-tone grey carpet that may have been there since the Eighties. The aisles were ludicrously wide, as if they still expected people to jostle, three deep, to rifle through the CD racks. Staff wore shapeless, branded black T-shirts, meaning that a genre expert in the basement was hard to separate from someone who only started last week. When I looked for the Beach Boys Smile deluxe box-set I only found a piece of plastic in the racks that said “please ask at counter”. If you can’t display a beautiful item like that, you’re not doing your job properly.

The vinyl section I couldn’t find at all, but I’m assuming that there is one, tucked away in a grotty corner for minorities. Except that fetishists such as me will go to Sounds of the Universe, a nearby shop that advertises its vinyl products in the window, which plays records if you want to hear them, and where you’re likely to hear something new, something to raise your pulse, rather than the Rihanna album that you just heard in a café or a cab five minutes ago. The way we consume music has changed completely in the past ten years, but you’d never know it from walking around HMV.

Last summer the Voices of East Anglia blog posted a set of photos of the original HMV Shop on Oxford Street through the years. They were quite beautiful. This shop is now a branch of Foot Locker, but the present HMV could pick up plenty of aesthetic tips from its heritage. From the exterior signage, to the listening booths, to the specialist sections (whatever the “Cosmopolitan Corner” and “Personal Export Lounge” were, you’d definitely want to hang out there), it looked inviting and exciting.

Record sales back then were buoyant enough to pay for the grand staircase in the middle of the store. The HMV Shop had been opened by the Gramophone Company in 1921, ten years before that label amalgamated with Columbia to form EMI, Britain’s most successful label. For decades it thrived, but the digital age has seen the market for physical music product drop precipitously. It isn’t HMV’s fault that Boney M’s Mary’s Boy Child sold 1.6 million copies inside a month in 1978, while Orson’s No Tomorrow notoriously reached No 1 with sales of fewer than 18,000 in 2006.

The key to HMV’s survival, even on a much-reduced scale, isn’t in a hankering for the past. Many shops — chain stores in particular — have struggled or disappeared in recent years. However, other shops are thriving. Last year I did a short trip around the country to check out the state of record shops. It was invigorating. With the exception of a couple, whose owners were in their dotage, all were staying afloat, and some were doing better business than ever before. It isn’t a myth that teenagers are buying vinyl and obsessing over it. Records are cool objects to own — anyone can have 20,000 songs dangling round their neck, but not everyone can own a limited edition White Stripes seven-inch or an original mono copy of Jimi Hendrix’s Are You Experienced?. These are desirable items and need to be sold in the right environment.

In Dalston, East London, two new record shops — the ramshackle Eldica and the well-appointed Kristina — have appeared in the past year or so. Down the road from them is Rough Trade East, a vast store, just a few years old, that has already become an institution. It has “world famous weekly mail-outs” on new releases, exclusive mixes and CDs on sale, an Album of the Month club (with invitations to members-only events), and in-store happenings that include book launches and debates on the future of pop.

Could HMV compete with Rough Trade? No, it has a bigger and broader customer base. Instead, it should let Rough Trade have a concession — after all, Rough Trade’s branches are way west and east of Oxford Street. HMV should act like it is the parent of Rough Trade, Kristina and Sounds of the Universe, because that’s exactly what it is. It should be proud of its history. The original store has a plaque on the wall that reads “Opened by Sir Edward Elgar in July 1921” — that’s impressive.

If vintage clothes can be bought in Selfridges, then why not vintage sections in HMV? There are plenty of second-hand dealers in London, working out of lock-ups or from home, who would not only have a ready supply of vintage vinyl but would love to have a Central London location in which to sell it. Some concessions could change on a bi-monthly basis, like an art show; bands could curate some departments, recommending their favourite music, and decorating the place as well as DJing or doing in-store shows. Domino Records ran its own radio station for a week last summer out of its offices in Wandsworth and it felt like an event — there’s no reason why HMV couldn’t do the same.

Beyond the CD racks HMV’s magazine section is an embarrassment. Yes, they stock the quarterly Elvis: the Man and his Music, which I buy every issue of, but they also stock Heat. Who would go into HMV to buy a celebrity gossip magazine? Borders, which used to be across Oxford Street from HMV, had an extensive magazine section, which is now entirely absent from any major West End store; you can buy Fantastic Man for an interview with Hot Chip’s Alexis Taylor from a stall in Islington, but nowhere on Oxford Street. It’s an open goal. Like the HMV of old, Borders was a destination purely for its magazine selection. Stock them and people will browse, spend time and probably end up buying before they leave. It gets customers through the door and, looking at the wide open spaces, HMV isn’t doing that right now.

Other than Rough Trade East, the shop that HMV should really be looking to for ideas is a few doors away. The basement of Topshop is like a crazy souk, only navigable through practice and feminine intuition, and within it are plenty of concessions, vintage areas and shops within shops. Topshop, which once appeared way below HMV on the cool register, has re-invented itself by moving quickly to get involved with designers and start-ups who are creating a bit of buzz. An example is Wah Nails, a super-hipster nail salon that has its main store in Dalston and now has a concession in Topshop. It opened in 2010; only a handful of blogs had written about it. Then a couple of months later there it was in Topshop.

Selling music isn’t quite like selling clothes, but HMV’s clumsy embracing of technology — dumping the CDs and vinyl to sell MP3 players and assorted hardware — is short-termist; there are plenty of other shops already doing just that. The internet, however, could provide it with some much-needed cool. Blogs have helped Topshop to get new items and ideas into the store before even keen fashion watchers know about them. HMV could look to aspirational, tastemaker sites such as Pitchfork and Popjustice to recommend music. Beyond that, there are plenty of well-written, enthusiastic music blogs that HMV could take a chance on. It’s a two-way street. At the moment nobody would want their music or playlists to be associated with HMV’s grubby-grey carpet-tiles.

It isn’t just about what you buy, but how you buy it. There is a café in the basement of Topshop. Rough Trade has a café and a bar too. If you can meet friends, chat over a coffee, swap notes on the latest sound sensations, and then purchase those sounds, having a seated social hub for groups of friends will bring in more revenue than lone customers wandering the empty aisles.

Again, HMV could look east and steal some ideas from the Pacific Social Club cafe on Clarence Road. The walls there are decorated with vintage 78-sleeves, and there is a stack of vinyl that you can put on yourself as you eat your banana and passion fruit on toast. The café could include listening posts, using Spotify and iTunes. There must be a way for HMV to work with these digital distributors.

The details can be discussed later. At the moment HMV is little more than a vast shop window for Amazon; you can browse the racks, make a mental note of what you want, then go home and buy it online slightly cheaper. It needs to change how it sells more than what it sells. Customers need to go in thinking of HMV’s expertise — they need to think of the shop in the way that people thought of John Peel. Anybody can buy what they already know from Amazon; they need a gatekeeper.

At £160 million in the red, it wouldn’t hurt HMV much more to take a chance on a revamp, splash a couple of million re-inventing the Oxford Street store, and hope that, like Topshop, it attains trendsetting status, with its influence trickling down to regional branches. Its one major advantage, and one that it hasn’t begun to capitalise on, is that people genuinely like HMV. They want it to survive. I don’t remember anyone getting particularly weepy over the demise of Zavvi, Tower, or even Virgin. HMV, like EMI or the BBC, is a British institution that’s fun to knock, but nobody would ever want it to disappear.

Wednesday, 20 June 2012

Barry Gibb and Barbra Streisand: 'Guilty'

Yet straight away, before a note was sung, there was an ego problem. Bee Gee manager Robert Stigwood demanded three quarters of the royalties; three Gibbs, one Streisand, he figured. "They all sound alike," she snapped. "How much for just one?" The compromise was that Barry alone would complete the album with her.

Though Streisand was famously exacting, Gibb soon found her to be a pussycat in the studio. The one thing that riled him was her habit of making two cups of tea with one teabag: "my roots are in Brooklyn, we came from a poor family" she protested, "you don't just use a teabag once and throw it out!"

Clearly, he was in awe of her. He excitedly demo'd a dozen songs inside a week (with the bulk of the demos available on itunes, we know the album was effectively eighty per cent finished in seven days; yes, he does sing "I am a woman in love" and, yes, it'll make you snigger). When Barbra invited Barry and wife Lynda to dinner at her ranch home they saw rats scuttling across the floor. Gibb was shocked but too timorous to point out that his host had an infestation: besides, he reckoned it wouldn't have done much for the creative process.

The first single from Guilty, Woman In Love, is all minor key, with an eastern European feel, and it sounded ageless as soon as it hit the airwaves. "Life is a moment in space - when the dream has gone, it’s a lonelier place" has been decribed as "metaphysical cheese" on Tom Ewing's Popular blog but for me it's one of the most desolate opening lines to any pop song, and Streisand is entirely believable as a middle-aged woman who refuses to give up on her elusive, lifelong dream - what world could exist beyond it? She'd rather not know.

One of Streisand's few quibbles was with the line "It's a right I defend, over and over again": bizarrely she was worried it would make her sound like a militant women's libber. Gibb was more concerned that Streisand's trademark Broadway technique of gliding from one note to the next was in total contrast to his staccato, r&b-led melodies. The title track put them to the test: Streisand handles the first verse and chorus, before Gibb comes in - "pulses racing, we stand alone" - riding an unexpected key change. He never sounded more leonine. A lush string section glides in to back up his audacity. By the second chorus, Streisand is gliding and swooping like a swallow as Gibb stands square, not a hair out of place. It's a very playful performance, light and quite beautiful.

The album contains a couple of makeweights in the showy Love Inside and Life Story, which includes the curiously culinary line "You boiled me over, now you're cold as ice." But all is forgiven on What Kind Of Fool, another duet which this time has Gibb chasing in between the stentorian Streisand's lead, and chastising a lost lover with a suitably heartbreaking melody.

Guilty went on to sell eight million copies. In 2005 there was a sequel, Guilty 2 (it would have been titled Guilty Pleasures but the London club of the same name objected) which traded the original album's crisp minimalism for a contemporary, fuller, Nashville slickness. The same year brought the 25th Anniversary Edition of the original. It included no outtakes which is a shame as, apart from two Gibb originals in Secrets and Carried Away (duly covered by Elaine Paige and Olivia Newton John respectively), there were unreleased recordings of Wilbert Harrison's Kansas City and The Beatles' Lady Madonna.

But there was a bonus DVD, which included live footage shot in Malibu, in 1986, of Guilty and an especially fragile What Kind Of Fool. The duo are all in white, so clean, all mutual respect. Gibb is the cowardly lion, Streisand is Miss Bighearted Brooklyn of 1980, the Jewish matriarch with a bowl of chicken soup for her younger charge. "Make it a crime to be lonely and sad" they coo, "make it a crime to be out in the cold." With blue-eyed soul this persuasive, they could teach the law commission a thing or two.

Saturday, 19 May 2012

Paul Williams 'Someday Man'

There's a Paul Williams documentary called Still Alive which has just come out in the States. Rumer has recorded his Travellin' Boy on her new album. So it seems a good time to take a look at his first solo album, Someday Man, a personal touchstone. I talked to Paul about it in 2001. Here's what he had to say.

"Some people always complain that their life is too short, so they hurry it along

Their worries drive them insane but they still go along for the ride

As for me, I have all the time in the world..."

It's early 1970, and Paul Williams and Roger Nichols have been writing a few songs together. Great songs, too, that saw them shaping up as a Goffin and King for listeners who had hung around soda fountains listening to Bobby Vee in their early teens. For Up On The Roof, there was Harper's Bizarre's The Drifter; for Oh No Not My Baby, read To Put Up With You by The American Breed. But while there was plenty of work rolling in, notching up hits was a different matter.

"We were just about convinced that we'd never have a smash single. We almost sank The Monkees with Someday Man - Listen To The Band on the B-side got more airplay." The release of Paul's debut album, then, was never likely to test the noblesse of that opening lyric. By the end of the following year, the Nichols/Williams team was America's most in-demand.

Nichols was from Missoula, Montana, a city at the convergence of five mountain ranges, spreading down the Clark Fork and Bitterroot rivers. In 1968 he released an album as evocative as his rural roots with brother and sister Melinda and Murray MacLeod. Roger Nichols And The Small Circle Of Friends came out on A&M with help from the cream of the West Coast - it was produced by Tommy LiPuma, engineered by Bruce Botnick, with Randy Newman and Van Dyke Parks in attendance. Nichols' lyricist was Tony Asher, and in many ways Small Circle is a lyrical sequel to Pet Sounds - a little older, a little wiser, an album for early twenty-somethings thinking of settling down, but still turning to Smokey Robinson songs for relationship advice.

The album didn't do too well (though it did sell 50,000 copies when it was re-issued in Japan in the nineties, encouraging a belated sequel), but A&M owner Herb Alpert was impressed enough to get Nichols a staff job as a songwriter for A&M publishing, which is where he was introduced to Paul Williams.

Paul Williams had a peripatetic childhood, born in Omaha, Nebraska, but constantly moving, changing schools (nine by the time he reached the ninth grade), thanks to his father's job in construction. Then his father was killed in a car crash and Paul was shipped off to live with an aunt and uncle. He quit singing in talent shows and became more interested in film and acting, actively pursuing a movie career when he reached 21.

Soon he was acting alongside John Gielgud and Rod Steiger in Tony Richardson's The Loved One. "I was suddenly living my dream, 23-years old playing a 13-year-old squeaky voiced genius." His looks - part cherub, part Jim Henson creation - meant he was made for character parts, usually a good deal younger than his real age. In The Chase (1965) he taunts Robert Redford with a snippet of one of his own tunes - which inspired Paul to write, if only for his own amusement. A few months later he unsuccessfully auditioned for The Monkees. Acting work was drying up, and a short-lived publishing deal with Ishmael Music, part of White Whale, ended after three months with Paul being told he had no future in music.

A chance meeting in 1967 with songwriter Biff Rose was the catalyst. Together they wrote Fill Your Heart, recorded by Tiny Tim and later David Bowie; they also got a publishing deal with A&M, whose head of publishing, Chuck Kaye, teamed Paul up with writer/arranger Roger Nichols. Paul recorded one patchy but worthwhile LP on Reprise with a short-lived group called The Holy Mackerel (with pre-Elvis Jerry Scheff on bass), which was released in '69 after they'd already split. It included a moody soft-psych track called Scorpio Red, as well as one bona fide classic, Bitter Honey, an ultra catchy co-write with Roger Nichols which presaged the uplifting melancholia that was to become their trademark. "Roger is the best thing that ever happened to me as a songwriter. I learned more about structure, discipline, quality and class from Roger Nichols than anyone I ever met. He made me feel like I was a real lyricist."

Owing Reprise one more album, Paul recorded Someday Man in '69 with Roger producing. The pair had already released a legendary publishers album, We've Only Just Begun, that was a beauty in its own right. On Someday Man, Williams' warm, intense vocals - like a reedier Gene Clark, with a similar emotional tug - are a perfect match for Nichols' soft magic: there's the baroque Americana of I Know You, and the incredible switches on Roan Pony from urban paranoia to panoramic dreamscape. Oboes and harps figure strongly. "It was really Roger's album," Paul modestly reckons, "he did everything, charts, player choices. I wasn't an artist yet, not as much as I would become in a few more years I think."

Yet the spirit of Someday Man is more in Paul's lyrics than anything, the generosity, humility and humanity. Truth and beauty. Really, it's a whole philosophy: "I wrote from my heart more than I realised." The Monkees' cover of the title song probably makes it the most familiar track. "Is it about me? I'm not sure. I think so. It's a song about trusting."

The critics' indifference to the record hardly seemed to matter as the Carpenters' recordings of the Nichols/Williams canon - starting with We've Only Just Begun - sent their publishing cheques into the stratosphere. The former was originally written for a bank, a jingle commissioned after one of the bank's executives heard Nichols' Small Circle of Friends album. It was written the day before the ad company's deadline. Then Richard Carpenter saw the ad, the Carpenters cut their version, it reached no.2 in the States, and was nominated for a Grammy. A swathe of classics followed: I Won't Last A Day Without You, Rainy Days And Mondays, Let Me Be The One. By 1973, Nichols and Williams had "gone our separate ways after several years of day-to-day contact. I was off chasing movie dreams. I had a huge ego and a performing career ahead of me and I was using and drinking so my perception may have been altered."

Bugsy Malone and Phantom Of The Paradise, plus a string of Radio 2 staples like An Old Fashioned Love Song, followed but somehow the magic and innocence of Someday Man wasn't to be repeated. "The sweet surprise is finding out that there are people around the world who really honour the work, really cherish the album. Me and Roger have been collaborating a bit, we both think we've got one more really good song in the partnership. You never know."

"Some people always complain that their life is too short, so they hurry it along

Their worries drive them insane but they still go along for the ride

As for me, I have all the time in the world..."

It's early 1970, and Paul Williams and Roger Nichols have been writing a few songs together. Great songs, too, that saw them shaping up as a Goffin and King for listeners who had hung around soda fountains listening to Bobby Vee in their early teens. For Up On The Roof, there was Harper's Bizarre's The Drifter; for Oh No Not My Baby, read To Put Up With You by The American Breed. But while there was plenty of work rolling in, notching up hits was a different matter.

"We were just about convinced that we'd never have a smash single. We almost sank The Monkees with Someday Man - Listen To The Band on the B-side got more airplay." The release of Paul's debut album, then, was never likely to test the noblesse of that opening lyric. By the end of the following year, the Nichols/Williams team was America's most in-demand.

Nichols was from Missoula, Montana, a city at the convergence of five mountain ranges, spreading down the Clark Fork and Bitterroot rivers. In 1968 he released an album as evocative as his rural roots with brother and sister Melinda and Murray MacLeod. Roger Nichols And The Small Circle Of Friends came out on A&M with help from the cream of the West Coast - it was produced by Tommy LiPuma, engineered by Bruce Botnick, with Randy Newman and Van Dyke Parks in attendance. Nichols' lyricist was Tony Asher, and in many ways Small Circle is a lyrical sequel to Pet Sounds - a little older, a little wiser, an album for early twenty-somethings thinking of settling down, but still turning to Smokey Robinson songs for relationship advice.

The album didn't do too well (though it did sell 50,000 copies when it was re-issued in Japan in the nineties, encouraging a belated sequel), but A&M owner Herb Alpert was impressed enough to get Nichols a staff job as a songwriter for A&M publishing, which is where he was introduced to Paul Williams.

Paul Williams had a peripatetic childhood, born in Omaha, Nebraska, but constantly moving, changing schools (nine by the time he reached the ninth grade), thanks to his father's job in construction. Then his father was killed in a car crash and Paul was shipped off to live with an aunt and uncle. He quit singing in talent shows and became more interested in film and acting, actively pursuing a movie career when he reached 21.

Soon he was acting alongside John Gielgud and Rod Steiger in Tony Richardson's The Loved One. "I was suddenly living my dream, 23-years old playing a 13-year-old squeaky voiced genius." His looks - part cherub, part Jim Henson creation - meant he was made for character parts, usually a good deal younger than his real age. In The Chase (1965) he taunts Robert Redford with a snippet of one of his own tunes - which inspired Paul to write, if only for his own amusement. A few months later he unsuccessfully auditioned for The Monkees. Acting work was drying up, and a short-lived publishing deal with Ishmael Music, part of White Whale, ended after three months with Paul being told he had no future in music.

Owing Reprise one more album, Paul recorded Someday Man in '69 with Roger producing. The pair had already released a legendary publishers album, We've Only Just Begun, that was a beauty in its own right. On Someday Man, Williams' warm, intense vocals - like a reedier Gene Clark, with a similar emotional tug - are a perfect match for Nichols' soft magic: there's the baroque Americana of I Know You, and the incredible switches on Roan Pony from urban paranoia to panoramic dreamscape. Oboes and harps figure strongly. "It was really Roger's album," Paul modestly reckons, "he did everything, charts, player choices. I wasn't an artist yet, not as much as I would become in a few more years I think."

Yet the spirit of Someday Man is more in Paul's lyrics than anything, the generosity, humility and humanity. Truth and beauty. Really, it's a whole philosophy: "I wrote from my heart more than I realised." The Monkees' cover of the title song probably makes it the most familiar track. "Is it about me? I'm not sure. I think so. It's a song about trusting."

The critics' indifference to the record hardly seemed to matter as the Carpenters' recordings of the Nichols/Williams canon - starting with We've Only Just Begun - sent their publishing cheques into the stratosphere. The former was originally written for a bank, a jingle commissioned after one of the bank's executives heard Nichols' Small Circle of Friends album. It was written the day before the ad company's deadline. Then Richard Carpenter saw the ad, the Carpenters cut their version, it reached no.2 in the States, and was nominated for a Grammy. A swathe of classics followed: I Won't Last A Day Without You, Rainy Days And Mondays, Let Me Be The One. By 1973, Nichols and Williams had "gone our separate ways after several years of day-to-day contact. I was off chasing movie dreams. I had a huge ego and a performing career ahead of me and I was using and drinking so my perception may have been altered."

Bugsy Malone and Phantom Of The Paradise, plus a string of Radio 2 staples like An Old Fashioned Love Song, followed but somehow the magic and innocence of Someday Man wasn't to be repeated. "The sweet surprise is finding out that there are people around the world who really honour the work, really cherish the album. Me and Roger have been collaborating a bit, we both think we've got one more really good song in the partnership. You never know."

Tuesday, 15 May 2012

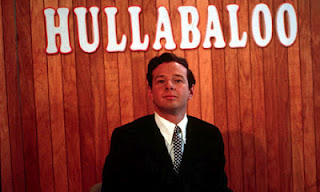

A conversation with Brian Matthew

Brian Matthew was there at the birth of British Rock'n'roll,

presenting Saturday

Club on the BBC's Light Programme. In the sixties he introduced the

Beatles to millions of BBC radio listeners, and even toured with them in the States. Today, Brian Matthew

still presents a

show in the same slot - he has been the host of Sounds Of The Sixties

since 1990, and has the highest listening

figures of any Radio 2 Saturday show, not bad when you consider the

octogenarian is up against the high-profile likes of Graham Norton and

Dermot

O'Leary. Over tea and sandwiches at his home in Kent, he told me that he

trained at RADA and had always planned to end up a TV producer.

Bob Stanley: You didn't initially want to be a DJ?

Brian Matthew: Not at all. I did forces radio in the army for a year, in Hamburg. It was all BBC equipment. We were based in what had been an old opera house, and lived in a hotel. The guys in charge there included Cliff Michelmore who was head of variety, and Raymond Baxter who was head of the announcing department. He'd not long been out of the RAF, a terribly hoo-ray chap. When he first met me he said 'There's only two things to remember - don't go on air drunk, and don't swear.' I thought crikey, what sort of set-up is this? Of course I broke all the rules. Not intentionally.

BS: I've read that you were at Hilversum too, which is a name I know from my parents' old radiogram, but I still don't really know where it is.

BM: After Hamburg I was at RADA, then I went straight into the Old Vic which is where I met Pamela (his wife - they married in 1951), and someone who worked for Hilversum, in the English department of Dutch radio. He gave me his number. When work was thin on the ground I called and he said 'Please go along to HMV on Oxford Street and record an audition, we want you to read some news. HMV will send us the disc, we've got an arrangement with them'. So I did, and we lived there, in Hilversum for two years. It was the centre for all Dutch radio. It was a funny old set-up, short wave radio, short wave only, and we broadcast the same 40 minute transmission three times a day to different areas - America, the far east.

Dutch radio was split up by five main companies, either religious or run by newspapers. So in effect you had a catholic station, a Conservative station, a Labour one, and a non-conformist one... I don't know what the fifth was. And they all had their own buildings around Hilversum. We had our own set-up in an old house, quite near to the others but not connected. Offices in one house, studios in another. We were there during the time of the enormous flood in 1953, large areas in a terrible state, loads of people killed. The American army came in. They gradually rebuilt the dykes, and came the time they were going to fill in the last block, it was quite a historic event. I was covering it so I learned everything I could about how it had been done. Needless to say I was repeating myself, but they put a copy of the recording in their archives.

BS: What happened between Hilversum and your first job at the BBC in 1955?

BM: We came back and lived with my parents in Coventry. I tried to get work at the Jaguar factory - they kept me hanging on, until one day I noticed there was a dairy across the road, advertising for work. So I was a milkman for six months. I used to go round in a lorry and collect milk from the farms. Then I worked in the dairy doing all the pasteurising, stacking up the next day's delivery in bottles and crates. It was pretty horrid.

While I was there I wrote to the BBC and asked if I could do a programme on Dutch jazz - they had a programme called World Of Jazz - and they said yes. The people in the dairy were very impressed, they said 'bloody hell, we've got a star working with us now!' and all that rubbish. The producer - who left under a bit of a cloud, but that's another story - he liked it and asked me to do a programme on English traditional jazz.

Within weeks I got an offer from Dunlop to edit their works magazine, in Kenilworth, which is not a bad place to live I must admit. And the BBC offered me a job as a trainee announcer, so I thought I'd go for that.

We found a flat in Willesden, quite a large flat, and lived there for a

couple of years on the princely salary of less than £20 a week. They

put me straight on to announcing, on all services - in those days it

was Home Service, Light Programme and Third Programme. You were usually

associated with one of them, but I did everything, I went from one to

another quite happily. Read the news, I did prom concerts...I always

liked the light music, big band jazz and that sort of thing. Johnny

Dankworth had a short series, only four programmes, with a huge

orchestra, a 27 piece band. Every week he had a guest classical

musician in the band, a viola player or whatever, and each week he'd

write a piece featuring this soloist. I did those with Johnny and we

became good friends. So I did three years an announcer, then I

thought I'd like to be a producer - I thought it might be a way in to

television, as a director.

We found a flat in Willesden, quite a large flat, and lived there for a

couple of years on the princely salary of less than £20 a week. They

put me straight on to announcing, on all services - in those days it

was Home Service, Light Programme and Third Programme. You were usually

associated with one of them, but I did everything, I went from one to

another quite happily. Read the news, I did prom concerts...I always

liked the light music, big band jazz and that sort of thing. Johnny

Dankworth had a short series, only four programmes, with a huge

orchestra, a 27 piece band. Every week he had a guest classical

musician in the band, a viola player or whatever, and each week he'd

write a piece featuring this soloist. I did those with Johnny and we

became good friends. So I did three years an announcer, then I

thought I'd like to be a producer - I thought it might be a way in to

television, as a director.

BS: You produced Saturday Club, starting in 1957. How did you end up presenting it?

BM: Jimmy Grant was their principal jazz producer. He was briefed to launch a programme called Skiffle Club which he asked me to introduce. I said I don't even know what skiffle is, he said that's alright, we'll manage. And it was an unbelievable runaway success, getting enormous listening figures. Management thought 'ullo, and asked Jim to do a two hour programme that would include skiffle but also has other elements of all this pop music that's emerging.

We had a

traditional jazz band and a modern jazz group as well. We ended up with

five groups a week that we recorded ourselves, and one live in the

studio on Saturday morning. We were very severely restricted on playing

records, what they called 'needle time', which I've never really

understood. Basically it was an agreement between the BBC and the record

companies that you would severely restrict the number of records in

order that you could continue to employ live musicians. And of course,

that's how the pirates shot from below everybody's feet and broke

all the rules by playing records all the time. And the BBC very soon

followed, thank goodness.

We had a

traditional jazz band and a modern jazz group as well. We ended up with

five groups a week that we recorded ourselves, and one live in the

studio on Saturday morning. We were very severely restricted on playing

records, what they called 'needle time', which I've never really

understood. Basically it was an agreement between the BBC and the record

companies that you would severely restrict the number of records in

order that you could continue to employ live musicians. And of course,

that's how the pirates shot from below everybody's feet and broke

all the rules by playing records all the time. And the BBC very soon

followed, thank goodness.

Anyway, I started Saturday Club and the Sunday morning programme Easybeat (from 1958), and they said 'we'd like you to start presenting these programmes as well as producing them.' I thought 'Wow, whoopee!', and after six years of that I got an offer to go on commercial radio as well, on Luxembourg, and went freelance. I can't believe the amount of work I was getting through. The BBC said we'd like you to carry on doing what you're doing. So eventually I was doing eight programmes a week on Luxembourg, Sundays I went up to Birmingham and televised Thank Your Lucky Stars (from 1961 to 1965), and produced a World Service programme. I was never at home, ever.

BS: Most of your radio work was on the Light Programme. What happened when it split into Radios 1 and 2 in 1967?

BM: I did Saturday Club for eight or nine years, until somebody in management - now dead, I'm happy to say in this instance - decided they were going to unite people with Radio 1, and that I wasn't really suited for that. So they cast me out. I went to see this chap and I said 'Are you really telling me I have no future in radio?' and he said 'Well yes, I think I am'. Fortunately an engineer I'd worked with on Saturday Club named Brian Willey had started to introduce a daily afternoon programme called Roundabout, with a different compere every day of the week. Brian gradually increased it until I was working five days a week, the only one there. It was what they now call drive time, 4.30 til 7. And I've not really been out of work since.

BS: The first time I remember hearing your voice was on My Top Twelve. Have you ever been on Desert Island Discs?

BM: Never. It's absolutely crackers! It never came up.

BS: That is crackers. So how did you end up presenting My Top Twelve?

BM: That was a surprise. Derek Chinnery was head of Radio 1. Out of the blue (in 1973) he came up with the idea, it was a good idea. Once in a while, someone would surprise me and choose all their own records! It was a weird eye-opener. I remember a My Top Twelve that I did do with Bill Haley. We were chatting about his whole life story. He admitted he'd had a serious drink problem, and that it had interfered with his work. Then suddenly he broke into tears in the interview, sobbing, because he'd made a mess of his life. We got it sorted out, that didn't go on air, but it was quite moving. He wasn't being sour grapes or anything, no reason why he should, but clearly thought he'd fouled it up. Which he had, to a large extent.

BS: I've heard that you found Nina Simone a bit of a handful.

BM: I interviewed her two or three times - this wasn't on My Top Twelve, though. The last time was an absolute disaster. I was a great admirer of her work, saw her at Ronnie's (Ronnie Scott's) and thought she was really great. She was always a bit tight. She got a bit quirky and peculiar because she felt, with a great deal of justification, that she'd been mistreated, mainly by record companies. So she had a great chip on her shoulder. We had her on Round Midnight and Robin the producer was devoted to her, he was thrilled to be meeting her. She came up from Ronnie's with a crowd - I think they were related to her, at least some of them were. He went up to her and said 'Delighted to meet you Miss Simone, may I call you Nina?' And she said 'No! You may not!'. I thought wow, we're off to a flying start here! She sat with her crowd in the control room and eventually one of these guys came in and said 'I want you to tell me the questions you're going to ask Miss Simone'. I said 'I'm not going to tell you. That's down to me, not down to you, I'm sorry we don't work like that'. And he looked a bit put out. So he went back and told her, there was a bit of a hoo-ha... She came in in a very, very black mood and gave me a rich two and a half minutes, it wasn't much, and then said she had to go back to Ronnie's. I said, fair enough. Robin rang and he booked a cab, and we all stood on the steps outside with nothing to say to each other, not too pleased with each other. I remember Robin was holding the cab door open for them and said 'Thank you very much Miss Simone. Fuck off" and slammed the door. I thought good for you, man! I never met her again, I'm happy to say. We were only promoting her appearance at the club. Dear God!

BS: Were any other guests that awkward?

BM: I didn't get to meet many people who pulled that angle, with high blown ideas of their own importance. It was a weird eye opener. I was booked to do a session with Brook Benton. Radio was quite different where he came from. He asked 'who's gonna put this out on disc?' - he really thought we were ripping him off, and he wasted half the session arguing about whether he was going to sing. He gave me a really hard time, but he came out with five songs in the end. Gene Vincent, he was alright, but he came in on Saturday Club swinging a knife and frightened me to death. This dagger he'd bought in Africa. It was just a thing he did, he didn't make any threatening gestures. But I was a bit put out.

BS: One of the better known Saturday Club sessions was with Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran. Where would that have been recorded?

BM: Piccadilly Theatre, round the back of a gentleman's outfitter. Vincent was first, then Cochran came in to do his session, who I must say was a thoroughly nice guy. Vincent got up to leave and Cochran shouted 'Hey Vincent, you ain't goin' anywhere. I got your crutches! You come and jam with me'. They did a twenty minute jam which was fabulous, at the end of which our recording engineer came out of his little booth and said 'was I supposed to record that?' Can you imagine? Twenty joyous minutes.

BS: During the Saturday Club years, did you think of yourself as a Beatles man or a Stones man?

BM: I thought very much I was on the Beatles side of the coin. But now I prefer playing Stones records. Although I found them much more difficult to get on with. Mick would always do a promotional chat, but he would not be very forthcoming. I found out after he died that Brian Jones was quite a fan. I had a nice letter from one of his family saying he had always spoken highly of me and I was totally surprised, because I never got them impression from meeting him. He was always very cagey. Keith I never got on with at all. I admire what he's done, quite substantially, but he was almost impossible for me to deal with. They were a closed shop, very inward looking.

BS: How well did you get on with the Beatles? Didn't you accompany them on an American tour?

BM: The Beatles were very extrovert - my only regret there is that I didn't have more to do with George who I thought was a lovely guy, absolutely lovely. I went to America with them for a week at Epstein's invitation and they were all pretty good. I never knew where I was with Lennon! Who did? But Paul was always very forthcoming. And I had one long conversation with George in a dressing room in Chicago, and I thought this guy's got a lot more than he's allowed to say. I don't mean not allowed but... the kind of general attitude was John and Paul did all the chat, and Ringo would make the odd comment from the background - he was always all right. But George. I've just seen the documentary his wife made, and I've been practically in tears thinking 'what an opportunity I missed there'. Only because he was obviously somebody that you really ought to know. Extremely talented too. Well, they all were! I'll make an exception for Ringo, he didn't pretend to be particularly talented.

BS: I've read that you and Brian Epstein were set to open a theatre together. What happened?

BM: I knew Brian Epstein very well - only through the Beatles. I met him when they first came to Broadcasting House, and we became extremely good friends. I dreamed up the idea of building a theatre in this area (Orpington, Kent) and the council agreed. They gave me a potential site at a place called High Elms, which is a huge woodland estate, and they would charge me a peppercorn rent. We could have built it for £24,000 - it's unbelievable now when you think about it. Brian said he'd arrange the raising of the funds and I'd run it. In the meantime, the theatre in Bromley burnt down and it was put about that I'd set fire to it. Absolute nonsense! It was raised in council meetings - I had a friend on the council. They said 'we don't want this Matthew chap building a theatre because we'll have our new one' - and their new one cost £3 million.

BS: Were you aware of what was going on in Brian Epstein's private life?

BM: I knew he was gay, but I didn't know he had quite serious problems in that area, which he had. I didn't know that he was so heavily into drugs, very, very hooked. And generally his life was a bit of a mess. Then the Beatles hooked up with that awful man in America, Allen Klein. A pretty fearsome man. When I was over there Brian said he had a meeting with him and would I like to come. Well, he had armed guards, literally, in this room in a baseball stadium. I don't know why, it was just his nature. I thought 'I don't like this man, he's poison.' Of course Brian didn't know what to make of it; he thought 'he can do things I can't do', which was true, unfortunately. Anyway, Klein got in there eventually and fouled it up for everybody. Poor old Brian. Very sad.

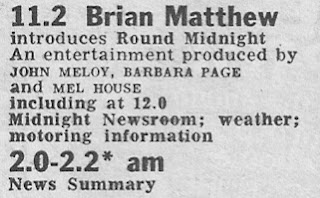

BS: From January 1978 until you took over Sounds Of The Sixties, you presented Round Midnight, which was an arts show.

BM: It was. That was its basic concept. That ran for thirteen years, 11 til 1, five nights a week. We did it as an audience show, live, from theatres all over the country and that was super, I really enjoyed that. We did a book every night, and some sort of entertainment - could be opera, could be ballet. And of course there was a substantial amount of music. We went to Edinburgh every year for a fortnight. And we did other theatres usually when they had a touring show with a big name. We went to Scarborough, Alan Ayckbourn was very keen. I couldn't believe it - that was one of the first we did and got an absolute full audience. In the middle of the night! In Scarborough! They didn't seem surprised, but I must admit I was.

BS: Forty five years after they said you had no future in broadcasting, what are your thoughts on Radio 1?

BM: I've never had much time for it, quite honestly. I don't like a lot of the style that's evolved from it. It obviously had some very good people on it. But they've had some crap as well.

Brian Matthew presents Sounds Of The Sixties on Radio 2 every Saturday morning between 8 and 10

There are more details on Brian's career at:

http://andywalmsley.blogspot.co.uk/2012/01/brian-matthew.html

Bob Stanley: You didn't initially want to be a DJ?

Brian Matthew: Not at all. I did forces radio in the army for a year, in Hamburg. It was all BBC equipment. We were based in what had been an old opera house, and lived in a hotel. The guys in charge there included Cliff Michelmore who was head of variety, and Raymond Baxter who was head of the announcing department. He'd not long been out of the RAF, a terribly hoo-ray chap. When he first met me he said 'There's only two things to remember - don't go on air drunk, and don't swear.' I thought crikey, what sort of set-up is this? Of course I broke all the rules. Not intentionally.

BS: I've read that you were at Hilversum too, which is a name I know from my parents' old radiogram, but I still don't really know where it is.

BM: After Hamburg I was at RADA, then I went straight into the Old Vic which is where I met Pamela (his wife - they married in 1951), and someone who worked for Hilversum, in the English department of Dutch radio. He gave me his number. When work was thin on the ground I called and he said 'Please go along to HMV on Oxford Street and record an audition, we want you to read some news. HMV will send us the disc, we've got an arrangement with them'. So I did, and we lived there, in Hilversum for two years. It was the centre for all Dutch radio. It was a funny old set-up, short wave radio, short wave only, and we broadcast the same 40 minute transmission three times a day to different areas - America, the far east.

Dutch radio was split up by five main companies, either religious or run by newspapers. So in effect you had a catholic station, a Conservative station, a Labour one, and a non-conformist one... I don't know what the fifth was. And they all had their own buildings around Hilversum. We had our own set-up in an old house, quite near to the others but not connected. Offices in one house, studios in another. We were there during the time of the enormous flood in 1953, large areas in a terrible state, loads of people killed. The American army came in. They gradually rebuilt the dykes, and came the time they were going to fill in the last block, it was quite a historic event. I was covering it so I learned everything I could about how it had been done. Needless to say I was repeating myself, but they put a copy of the recording in their archives.

BS: What happened between Hilversum and your first job at the BBC in 1955?

BM: We came back and lived with my parents in Coventry. I tried to get work at the Jaguar factory - they kept me hanging on, until one day I noticed there was a dairy across the road, advertising for work. So I was a milkman for six months. I used to go round in a lorry and collect milk from the farms. Then I worked in the dairy doing all the pasteurising, stacking up the next day's delivery in bottles and crates. It was pretty horrid.

While I was there I wrote to the BBC and asked if I could do a programme on Dutch jazz - they had a programme called World Of Jazz - and they said yes. The people in the dairy were very impressed, they said 'bloody hell, we've got a star working with us now!' and all that rubbish. The producer - who left under a bit of a cloud, but that's another story - he liked it and asked me to do a programme on English traditional jazz.

Within weeks I got an offer from Dunlop to edit their works magazine, in Kenilworth, which is not a bad place to live I must admit. And the BBC offered me a job as a trainee announcer, so I thought I'd go for that.

We found a flat in Willesden, quite a large flat, and lived there for a

couple of years on the princely salary of less than £20 a week. They

put me straight on to announcing, on all services - in those days it

was Home Service, Light Programme and Third Programme. You were usually

associated with one of them, but I did everything, I went from one to

another quite happily. Read the news, I did prom concerts...I always

liked the light music, big band jazz and that sort of thing. Johnny

Dankworth had a short series, only four programmes, with a huge

orchestra, a 27 piece band. Every week he had a guest classical

musician in the band, a viola player or whatever, and each week he'd

write a piece featuring this soloist. I did those with Johnny and we

became good friends. So I did three years an announcer, then I

thought I'd like to be a producer - I thought it might be a way in to

television, as a director.

We found a flat in Willesden, quite a large flat, and lived there for a

couple of years on the princely salary of less than £20 a week. They

put me straight on to announcing, on all services - in those days it

was Home Service, Light Programme and Third Programme. You were usually

associated with one of them, but I did everything, I went from one to

another quite happily. Read the news, I did prom concerts...I always

liked the light music, big band jazz and that sort of thing. Johnny

Dankworth had a short series, only four programmes, with a huge

orchestra, a 27 piece band. Every week he had a guest classical

musician in the band, a viola player or whatever, and each week he'd

write a piece featuring this soloist. I did those with Johnny and we

became good friends. So I did three years an announcer, then I

thought I'd like to be a producer - I thought it might be a way in to

television, as a director. BS: You produced Saturday Club, starting in 1957. How did you end up presenting it?

BM: Jimmy Grant was their principal jazz producer. He was briefed to launch a programme called Skiffle Club which he asked me to introduce. I said I don't even know what skiffle is, he said that's alright, we'll manage. And it was an unbelievable runaway success, getting enormous listening figures. Management thought 'ullo, and asked Jim to do a two hour programme that would include skiffle but also has other elements of all this pop music that's emerging.

We had a

traditional jazz band and a modern jazz group as well. We ended up with

five groups a week that we recorded ourselves, and one live in the

studio on Saturday morning. We were very severely restricted on playing

records, what they called 'needle time', which I've never really

understood. Basically it was an agreement between the BBC and the record

companies that you would severely restrict the number of records in

order that you could continue to employ live musicians. And of course,

that's how the pirates shot from below everybody's feet and broke

all the rules by playing records all the time. And the BBC very soon

followed, thank goodness.

We had a

traditional jazz band and a modern jazz group as well. We ended up with

five groups a week that we recorded ourselves, and one live in the

studio on Saturday morning. We were very severely restricted on playing

records, what they called 'needle time', which I've never really

understood. Basically it was an agreement between the BBC and the record

companies that you would severely restrict the number of records in

order that you could continue to employ live musicians. And of course,

that's how the pirates shot from below everybody's feet and broke

all the rules by playing records all the time. And the BBC very soon

followed, thank goodness.Anyway, I started Saturday Club and the Sunday morning programme Easybeat (from 1958), and they said 'we'd like you to start presenting these programmes as well as producing them.' I thought 'Wow, whoopee!', and after six years of that I got an offer to go on commercial radio as well, on Luxembourg, and went freelance. I can't believe the amount of work I was getting through. The BBC said we'd like you to carry on doing what you're doing. So eventually I was doing eight programmes a week on Luxembourg, Sundays I went up to Birmingham and televised Thank Your Lucky Stars (from 1961 to 1965), and produced a World Service programme. I was never at home, ever.

BS: Most of your radio work was on the Light Programme. What happened when it split into Radios 1 and 2 in 1967?

BM: I did Saturday Club for eight or nine years, until somebody in management - now dead, I'm happy to say in this instance - decided they were going to unite people with Radio 1, and that I wasn't really suited for that. So they cast me out. I went to see this chap and I said 'Are you really telling me I have no future in radio?' and he said 'Well yes, I think I am'. Fortunately an engineer I'd worked with on Saturday Club named Brian Willey had started to introduce a daily afternoon programme called Roundabout, with a different compere every day of the week. Brian gradually increased it until I was working five days a week, the only one there. It was what they now call drive time, 4.30 til 7. And I've not really been out of work since.

BS: The first time I remember hearing your voice was on My Top Twelve. Have you ever been on Desert Island Discs?

BM: Never. It's absolutely crackers! It never came up.

BS: That is crackers. So how did you end up presenting My Top Twelve?

BM: That was a surprise. Derek Chinnery was head of Radio 1. Out of the blue (in 1973) he came up with the idea, it was a good idea. Once in a while, someone would surprise me and choose all their own records! It was a weird eye-opener. I remember a My Top Twelve that I did do with Bill Haley. We were chatting about his whole life story. He admitted he'd had a serious drink problem, and that it had interfered with his work. Then suddenly he broke into tears in the interview, sobbing, because he'd made a mess of his life. We got it sorted out, that didn't go on air, but it was quite moving. He wasn't being sour grapes or anything, no reason why he should, but clearly thought he'd fouled it up. Which he had, to a large extent.

BS: I've heard that you found Nina Simone a bit of a handful.

BM: I interviewed her two or three times - this wasn't on My Top Twelve, though. The last time was an absolute disaster. I was a great admirer of her work, saw her at Ronnie's (Ronnie Scott's) and thought she was really great. She was always a bit tight. She got a bit quirky and peculiar because she felt, with a great deal of justification, that she'd been mistreated, mainly by record companies. So she had a great chip on her shoulder. We had her on Round Midnight and Robin the producer was devoted to her, he was thrilled to be meeting her. She came up from Ronnie's with a crowd - I think they were related to her, at least some of them were. He went up to her and said 'Delighted to meet you Miss Simone, may I call you Nina?' And she said 'No! You may not!'. I thought wow, we're off to a flying start here! She sat with her crowd in the control room and eventually one of these guys came in and said 'I want you to tell me the questions you're going to ask Miss Simone'. I said 'I'm not going to tell you. That's down to me, not down to you, I'm sorry we don't work like that'. And he looked a bit put out. So he went back and told her, there was a bit of a hoo-ha... She came in in a very, very black mood and gave me a rich two and a half minutes, it wasn't much, and then said she had to go back to Ronnie's. I said, fair enough. Robin rang and he booked a cab, and we all stood on the steps outside with nothing to say to each other, not too pleased with each other. I remember Robin was holding the cab door open for them and said 'Thank you very much Miss Simone. Fuck off" and slammed the door. I thought good for you, man! I never met her again, I'm happy to say. We were only promoting her appearance at the club. Dear God!

BS: Were any other guests that awkward?

BM: I didn't get to meet many people who pulled that angle, with high blown ideas of their own importance. It was a weird eye opener. I was booked to do a session with Brook Benton. Radio was quite different where he came from. He asked 'who's gonna put this out on disc?' - he really thought we were ripping him off, and he wasted half the session arguing about whether he was going to sing. He gave me a really hard time, but he came out with five songs in the end. Gene Vincent, he was alright, but he came in on Saturday Club swinging a knife and frightened me to death. This dagger he'd bought in Africa. It was just a thing he did, he didn't make any threatening gestures. But I was a bit put out.

BS: One of the better known Saturday Club sessions was with Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran. Where would that have been recorded?

BM: Piccadilly Theatre, round the back of a gentleman's outfitter. Vincent was first, then Cochran came in to do his session, who I must say was a thoroughly nice guy. Vincent got up to leave and Cochran shouted 'Hey Vincent, you ain't goin' anywhere. I got your crutches! You come and jam with me'. They did a twenty minute jam which was fabulous, at the end of which our recording engineer came out of his little booth and said 'was I supposed to record that?' Can you imagine? Twenty joyous minutes.

BS: During the Saturday Club years, did you think of yourself as a Beatles man or a Stones man?

BM: I thought very much I was on the Beatles side of the coin. But now I prefer playing Stones records. Although I found them much more difficult to get on with. Mick would always do a promotional chat, but he would not be very forthcoming. I found out after he died that Brian Jones was quite a fan. I had a nice letter from one of his family saying he had always spoken highly of me and I was totally surprised, because I never got them impression from meeting him. He was always very cagey. Keith I never got on with at all. I admire what he's done, quite substantially, but he was almost impossible for me to deal with. They were a closed shop, very inward looking.

BS: How well did you get on with the Beatles? Didn't you accompany them on an American tour?

BM: The Beatles were very extrovert - my only regret there is that I didn't have more to do with George who I thought was a lovely guy, absolutely lovely. I went to America with them for a week at Epstein's invitation and they were all pretty good. I never knew where I was with Lennon! Who did? But Paul was always very forthcoming. And I had one long conversation with George in a dressing room in Chicago, and I thought this guy's got a lot more than he's allowed to say. I don't mean not allowed but... the kind of general attitude was John and Paul did all the chat, and Ringo would make the odd comment from the background - he was always all right. But George. I've just seen the documentary his wife made, and I've been practically in tears thinking 'what an opportunity I missed there'. Only because he was obviously somebody that you really ought to know. Extremely talented too. Well, they all were! I'll make an exception for Ringo, he didn't pretend to be particularly talented.

BS: I've read that you and Brian Epstein were set to open a theatre together. What happened?

BM: I knew Brian Epstein very well - only through the Beatles. I met him when they first came to Broadcasting House, and we became extremely good friends. I dreamed up the idea of building a theatre in this area (Orpington, Kent) and the council agreed. They gave me a potential site at a place called High Elms, which is a huge woodland estate, and they would charge me a peppercorn rent. We could have built it for £24,000 - it's unbelievable now when you think about it. Brian said he'd arrange the raising of the funds and I'd run it. In the meantime, the theatre in Bromley burnt down and it was put about that I'd set fire to it. Absolute nonsense! It was raised in council meetings - I had a friend on the council. They said 'we don't want this Matthew chap building a theatre because we'll have our new one' - and their new one cost £3 million.

BS: Were you aware of what was going on in Brian Epstein's private life?

BM: I knew he was gay, but I didn't know he had quite serious problems in that area, which he had. I didn't know that he was so heavily into drugs, very, very hooked. And generally his life was a bit of a mess. Then the Beatles hooked up with that awful man in America, Allen Klein. A pretty fearsome man. When I was over there Brian said he had a meeting with him and would I like to come. Well, he had armed guards, literally, in this room in a baseball stadium. I don't know why, it was just his nature. I thought 'I don't like this man, he's poison.' Of course Brian didn't know what to make of it; he thought 'he can do things I can't do', which was true, unfortunately. Anyway, Klein got in there eventually and fouled it up for everybody. Poor old Brian. Very sad.

BS: From January 1978 until you took over Sounds Of The Sixties, you presented Round Midnight, which was an arts show.

BM: It was. That was its basic concept. That ran for thirteen years, 11 til 1, five nights a week. We did it as an audience show, live, from theatres all over the country and that was super, I really enjoyed that. We did a book every night, and some sort of entertainment - could be opera, could be ballet. And of course there was a substantial amount of music. We went to Edinburgh every year for a fortnight. And we did other theatres usually when they had a touring show with a big name. We went to Scarborough, Alan Ayckbourn was very keen. I couldn't believe it - that was one of the first we did and got an absolute full audience. In the middle of the night! In Scarborough! They didn't seem surprised, but I must admit I was.

BS: Forty five years after they said you had no future in broadcasting, what are your thoughts on Radio 1?

BM: I've never had much time for it, quite honestly. I don't like a lot of the style that's evolved from it. It obviously had some very good people on it. But they've had some crap as well.

Brian Matthew presents Sounds Of The Sixties on Radio 2 every Saturday morning between 8 and 10

There are more details on Brian's career at:

http://andywalmsley.blogspot.co.uk/2012/01/brian-matthew.html

Sunday, 22 April 2012

Gene Vincent: the road is rocky

The more time goes by, the more it seems to me that Gene Vincent has the strongest claim to be the ultimate 50s rocker. Certainly he was the biker's choice. For a start he had the tortured, twisted look, the ever-greasy collapsing pompadour. He seemed shy but overloaded with pent-up aggression, and the only way he could find release was in hard liquor and harsh, chain-swinging songs about gals in red blue jeans. This was the image; you don't hear many stories to suggest it wasn't close to the truth.

The more time goes by, the more it seems to me that Gene Vincent has the strongest claim to be the ultimate 50s rocker. Certainly he was the biker's choice. For a start he had the tortured, twisted look, the ever-greasy collapsing pompadour. He seemed shy but overloaded with pent-up aggression, and the only way he could find release was in hard liquor and harsh, chain-swinging songs about gals in red blue jeans. This was the image; you don't hear many stories to suggest it wasn't close to the truth.Originally he was Eugene Vincent Craddock, a native of Norfolk, Virginia who didn't seem to like much beyond motorbikes and girls, and whose life was entirely unremarkable until the summer of 1955 when two events changed it forever. In July he was involved in a bike crash, one so bad that his left leg was almost severed below the knee. Then in September, with his whole leg in plaster, Gene went to see Elvis Presley play in Norfolk and had his mind blown. Elvis literally had his clothes torn off by rabid fans that night. Gene went home, picked up his guitar, and wrote Be Bop A Lula which he debuted at local radio station WCMS's talent show in January '56. By July it was a US Top Ten hit and Vincent was in demand, criss-crossing the States with his band the Blue Caps. His short life was suddenly mapped out for him.

Vincent's Blue Caps rocked raw, more desperately than anyone - listen again to Cliff Gallup's outrageous solos on the over-familiar Be Bop A Lula. It's an incredibly sexy record - Buddy Holly had melodic, romantic nous and Little Richard had balls-on-the-line freak energy, but neither made a record that was as intense and panting as Be Bop A Lula. Gene can't wait to tell us about what he's got. She's the gal in the red blue jeans, queen of all the teens, clearly a looker, then he sings "she's the woman that I know". From gal to woman in one verse. With that carnal clue, the song pauses, followed by an untamed, unplanned shriek from the drummer. This and the prophetic, breakneck Race With The Devil were both recorded at Vincent's debut studio session; unsociable and ferocious, these early recordings are very hard to beat.

And, truthfully, Gene Vincent never bettered them, though that's no reason to ignore the rest of his career. While the Blue Caps Mark One rapidly disintegrated, later line-ups still cut hard rocking classics; Lotta Lovin', Cat Man, Who Slapped John, the delirious B-I-Bickey-Bi-Bo-Bo-Boo, the slo-mo menace of Baby Blue. Live they were a very tough act; Gene's pose rarely changed, legs apart, gripping the microphone stand as if he might collapse, always looking at some imaginary saviour in the balcony. Footage survives of Tex Ritter's Town Hall Party TV show, and the Blue Caps - with Johnny Meeks now on lead guitar - look magnificent in pink peg slacks, perfectly bequiffed; the pace at which they play was probably down to the diet pills Gene lived on. They also appeared in a film called Hot Rod Gang (1958) about a drag racer who joins a rock 'n' roll band (with assistance from Gene in a brief, not too embarrassing, acting role) to make enough money to race. But in spite of Hot Rod Gang and incessant touring, record sales were constantly declining and by the end of the decade Gene Vincent's career seemed washed up.

Now you may think all this was a lot of activity for a man who had nearly lost his leg, and you'd be right. During a season in Las Vegas he threw himself around so much on stage that he had to have a metal plate permanently inserted. Pretty soon, his finances were in equally bad shape and, midway through one tour, he absconded to Alaska with all the band's money.

Jack Good, the TV impresario who gave us Oh Boy! and basically invented Pop TV as we know it, was Gene's saviour. At a time when most had dismissed him as a one hit wonder, Good understood that he was a true great and brought him to Britain in '59. He loved the singer's outsider image and convinced him to lose his natty threads, decking him out in black leather. But when Gene appeared on ITV's Boy Meets Girls he hid his leg injury well, much to Good's chagrin - from the wings he was heard to shout "Limp, you bugger, limp!"

On a British tour with Eddie Cochran in 1960, Vincent played the hapless older brother to Cochran's cocksure pin-up. After one show they dived into a car as fans tore at them - it was only after they'd been travelling a while that Gene, hunched in the back seat, whispered "Eddie... Eddie... they got my pants."

It was also on this tour that Vincent was involved in a car crash near Chippenham, Wiltshire; he survived, but it caused more damage to his twisted leg. A local policeman, PC David Harman, was the first to the scene, where he discovered the crash had killed Cochran, Vincent's co-star and best friend. Unbelievably, the tour continued. In Glasgow he was in terrible pain and rubbed his left shoulder throughout the show before collapsing - doctors then discovered he'd broken his collar bone in the crash. To get out of the rest of the tour, Vincent forged a telegram that said his daughter Melody had died of pneumonia. By the time the promoters found she was alive and well, Vincent was back in the States.

Touring income aside, Jack Good provided a new string of Abbey Road-produced UK hits - Pistol Packin' Mama, I'm Goin' Home To See My Baby, She She Little Sheila; with Joe Moretti on guitar (Shakin' All Over, Brand New Cadillac) and Georgie Fame on piano, they were punchy, fizzy, and outshone pretty much all the early sixties UK competition. By the time he recorded Ivor Raymonde's dire Humpity Dumpity in '63, though, the spark was gone from Vincent's UK career too. Always one to make his life as complex as possible, he had fallen into Don Arden's management clutches, and an ill thought out quickie divorce added to his trouble. With all this, no hits on the horizon and an unpaid tax bill looming, he bailed out of Britain in 1965.

His late sixties recordings were a mixed bag, often underwhelming, but an album cut in '66 - only released in the UK on the London label, and simply called Gene Vincent - is a real gem. It was recorded at Sunset Sound Recorders in Los Angeles, where he now lived in a duplex with South African singer Jackie Frisco (right). The Wrecking Crew are all present - Hal Blaine on drums, Al Casey and Glen Campbell on guitar, and Larry Knechtel providing the wailing harmonica that kicks off Bird Doggin', his best single in years. The autobiographical Born To Be A Rolling Stone, the gorgeous Lonely Street, and chiming folk-rocker Love Is A Bird (written by Jimmy Seals, formerly of the Champs, later of Seals & Crofts) are up with his very best. PC David Harman, meanwhile, had by now changed his name to Dave Dee and given up the day job - he was scoring his first Top 10 hit, Hold Tight, with Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Tich, while Gene's fierce garage rocker Bird Doggin' failed to make any headway.

His late sixties recordings were a mixed bag, often underwhelming, but an album cut in '66 - only released in the UK on the London label, and simply called Gene Vincent - is a real gem. It was recorded at Sunset Sound Recorders in Los Angeles, where he now lived in a duplex with South African singer Jackie Frisco (right). The Wrecking Crew are all present - Hal Blaine on drums, Al Casey and Glen Campbell on guitar, and Larry Knechtel providing the wailing harmonica that kicks off Bird Doggin', his best single in years. The autobiographical Born To Be A Rolling Stone, the gorgeous Lonely Street, and chiming folk-rocker Love Is A Bird (written by Jimmy Seals, formerly of the Champs, later of Seals & Crofts) are up with his very best. PC David Harman, meanwhile, had by now changed his name to Dave Dee and given up the day job - he was scoring his first Top 10 hit, Hold Tight, with Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Tich, while Gene's fierce garage rocker Bird Doggin' failed to make any headway. Another obscurity worth digging out, as you fight your way past Be Bop A Lula '62 and Be Bop A Lula '69, is Our Souls (try saying it fast) from his final album, apparently written by his father-in-law. Always the lonesome fugitive, it was Vincent's kiss-off to a world that he must felt had it in for him.

In 1961 he had fallen down thirty concrete steps at a theatre in Newcastle and knocked himself unconscious; in '66 doctors in New Mexico decided to amputate his bad leg, but he fled the hospital in his pyjamas; in '69 he was mugged in his Paris hotel room.

Also in 1969 John Peel signed Vincent to his newly formed Dandelion label - incongruously he became a labelmate of Bridget St John and Medicine Head: sessions produced by Kim Fowley were disappointing, though a duet of Scarlet Ribbons with Linda Ronstadt stands out for its weirdness. He performed at the John and Yoko-sponsored Toronto Rock'n'Roll Festival, backed the Alice Cooper band, in September '69. Heavy drinking made for a shambolic show. At the end of the year he was back in Britain, touring dance halls which were appreciative but mostly small time. His backing group by now was a Croydon rock revivalist act called the Wild Angels and the BBC caught the first few days - including fumbling rehearsals in a pub basement, walls lined with used mattresses, Gene very patient with his amateurish young charges - on a beautiful but melancholy documentary.

He was broke again: at one point in the film Gene has to explain to a hotel receptionist that he is sharing a room with his roadie. On the backstage stairs of a venue in Ryde on the Isle of Wight, he stands exhausted, barely able to catch his breath after one last encore. He comes across as noble, sweet, but entirely defeated. Ravaged by booze, pills and his run of near-fatal accidents, he finally died of a perforated ulcer eighteen months later.

Thursday, 12 April 2012

The Girls, and other girls with guitars

If female pop singers were regarded as such an insignificant novelty in the sixties, it was ten times harder for female musicians to be taken seriously. Oddly this hadn't been a problem in blues circles where guitarists Memphis Minnie and Sister Rosetta Tharpe had been treated as equals. Likewise with folk, where Joan Baez, then Joni Mitchell, encouraged just as many women to pick up a guitar as Bob Dylan.

But rock 'n' roll was something else. The early sixties saw the huge boom in Girl Groups, propagated by the work of Phil Spector via The Crystals, Paris Sisters, and Ronettes: three girls singing in harmony, with a cavernous drum sound and a pair of castanets, was the du jour American sound of '63 - The Shirelles, Chiffons and Shangri La's racked up scores of hits. Ultimately, there were The Supremes. The records were often written for young women by young women (Carole King, Ellie Greenwich and Cynthia Weil), but the musicians were very rarely female; 90% of these records were played and produced by men.

The Beatles may not have gone a bundle on Sylvie Vartan, but Stateside they caused an explosion in the number of guitars bought by teenagers, plenty of whom were girls. In Boston, the Pandoras formed because they thought being in a band was, with a neat sideways logic, the easiest way for them to get to meet The Beatles. In Los Angeles, the classically educated Sandoval Sisters swapped their violins for Fender Jaguars and Rickenbackers after seeing the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show, and changed their name, with devastatingly naive arrogance, to the Girls (right). Their debut single, the Mann/Weil-written Chico's Girl, is a post Shangri La's bad-boy-good-girl melodrama which ranks as one of the dozen finest 45s of the Girl Group genre - and they actually played on it.

The Beatles may not have gone a bundle on Sylvie Vartan, but Stateside they caused an explosion in the number of guitars bought by teenagers, plenty of whom were girls. In Boston, the Pandoras formed because they thought being in a band was, with a neat sideways logic, the easiest way for them to get to meet The Beatles. In Los Angeles, the classically educated Sandoval Sisters swapped their violins for Fender Jaguars and Rickenbackers after seeing the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show, and changed their name, with devastatingly naive arrogance, to the Girls (right). Their debut single, the Mann/Weil-written Chico's Girl, is a post Shangri La's bad-boy-good-girl melodrama which ranks as one of the dozen finest 45s of the Girl Group genre - and they actually played on it. Pre-Beatles there had been a few maverick girls with guitars. Country singer Wanda Jackson was surrounded by older men telling her what to wear, what to say and what to sing until she crossed paths with hillbilly singer Elvis Presley in 1955. He convinced her that she had the voice for rock 'n' roll and Wanda duly obliged with gale-force rockers like Fujiyama Mama and Honey Bop. She painted her name on her acoustic. Off came the fringed suede jacket, too. Her new raunchy, heavy-lidded, high-heeled image went down particularly badly when she played Nashville's Grand Ole Opry where country bruiser Ernest Tubb insisted she couldn't show her shoulders. Wanda was so angry she could hardly sing.

On the rhythm and blues side Bo Diddley, a paternal, philanthropic rocker, assumed correctly that most people would rather watch musicians with accentuated femininity than a bunch of paunchy blokes; to this end he tutored a string of women to play guitar alongside him. The greatest was Norma-Jean Wofford, his amazonian half-sister (at least that's what told male admirers to keep them at bay) - she was renamed the Duchess (left). For good measure, the Bo-ettes provided backing vocals for Diddley. Footage of them on pop exploitation film The TAMI Show from 1964 shows just how mesmerising they were on stage, and makes their fellow performers - the full flower of mid-sixties pop from the Stones to the Beach Boys to the Supremes - look like so much less fun.